The purpose of many data science projects is to end up with a model that can be used within an organisation to solve a particular problem. If this is our case, we need to determine the right representation of that model so it can be shared in the easiest, cheapest, and most effective way. Web data products are an ideal vehicle for delivering machine learning models. The Web can be accessed almost everywhere and by multiple users. Moreover, the typical web application deployment cycle allows us to do easy updates.

You can check this tutorial on its GitHub repo.

This tutorial will make use of some of the techniques we used to build a sentiment classifier in a previous notebook. We will repeat the code here, since we are using a different algorithm (random forest, a type of tree-based classifier), together with some improvements on model selection. But if you are interested about the fundamentals of a linear classifier model, and how to build it using Python, have a look at that tutorial.

In order to build a web-based product we will use Shiny a web development framework and application server for the R language. This might seem counterintuitive at first. The R language is not the best language for software design or enterprise systems. But if our web application requirements are simple enough, we can benefit of well known architectural patterns such as Model-View-Controller being implemented in the framework and leave us just with the task of defining the necessary user interface elements and their interactions with our R models and data structures.

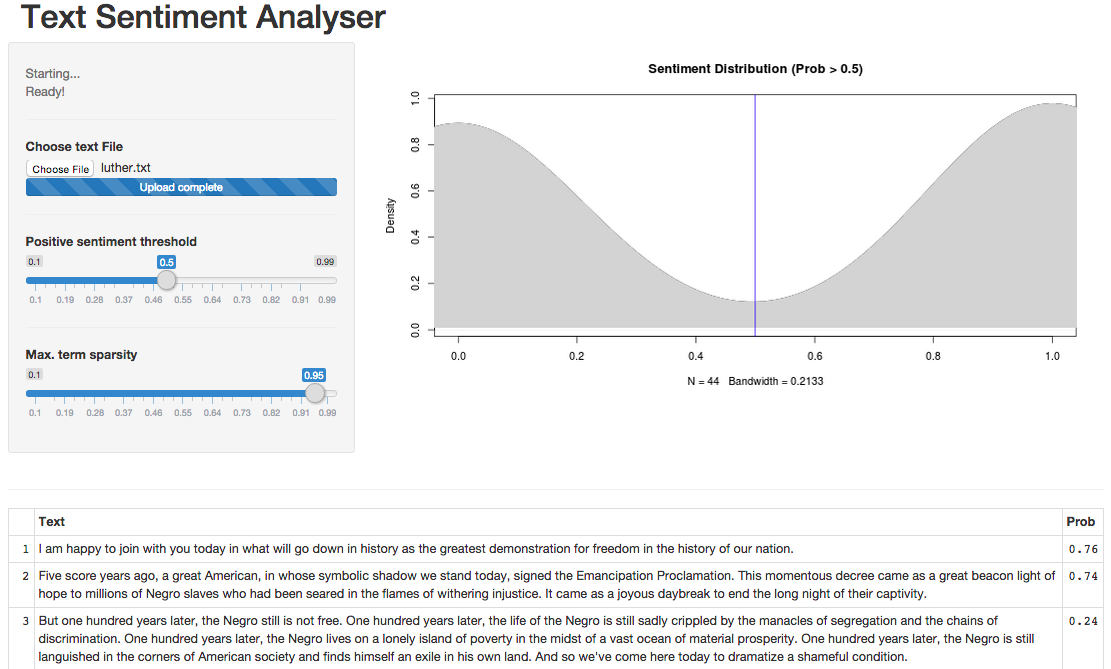

In the end, we will end up building an application like this one. All the code is available in our data science with R and Python repo. Hopefully you will find it exciting!

Note: the app hosted at Shinyapps.io is running on a free account. That means that is very restricted in computational resources and will show to be not responsible either when a lot of connections are made, or when large files / large number of trees are used. The best way to follow the tutorial is to try the app yourself locally using RStudio.

Building a classifier

The sentiment classifier we will build here has a peculiarity. Normally we will use a training dataset to train our model and use the resulting model as it is to predict any new input data. In the case of a sentiment classifier that means that the model will decide on the most relevant terms to build the classifier from tose in the training set, filtering also out the less frequent ones based on a sparsity coefficient. Once we have that model ready, when classifying new text, the previous terms will searched for in the new data in order to classify the text properly.

Of course we face the problem that the new data could not include most of these terms and therefore our classifier won’t have many chances of doing a good sentiment interpretation. Also we will end up with a model potentially including many variables that aren’t really useful. This problem doesn’t happen when we are classifying data with a well defined set of variables, but with text we need to find a trade-off between including all the words in a given language (something impossible) and including just a subset of the most important ones to define a text sentiment. The problem is even worse when our training data is not large enough. A large and heterogeneous training corpus will make a better job at finding the right terms. But our training data is very modest and comes mostly from social media posts.

So this is what we are going to do. We will apply a higher sparsity value to the training data. This will be translated to ending up with many more terms than normal. Then, once we have the incoming new data that we want to classify, we will build a separate corpus with the most frequent terms within it. Then we intersect both corpora. This will guarantee that we use just terms in the training set that appear in the new data, making all the terms in the resulting model useful. The drawback is that we will need to re-train the model every time new data comes in, so the classification process will take longer in order to be more accurate (since it includes the training and the classification). Therefore, our web classifier will work for not too big datasets (e.g. something like the size of an email or a page or two of text).

The complete server.R code will include all the code in this section, in the right order, but we are going to explain it here piece by piece. Therefore this code is not intended to be executed in sequence or whatsoever. It is just an explanation of part of the code that we will include our server.R.

Pre-loading training data

So frrst things first. We need to preload the training corpus. This code will be executed just once. The resulting data frame will be reused every time we want to train a classifier.

First we load the training data from a tab-separated file.

train_data_df <- read.csv(

file = 'train_data.tsv',

sep='\t',

quote = "",

header=FALSE,

stringsAsFactor=F,

col.names=c("Sentiment", "Text")

)

train_data_df$Sentiment <- as.factor(train_data_df$Sentiment)Once we have the training data in a data frame, we can build a training corpus, as we explained in our sentiment classification notebook.

# Create training corpus for later re-use

train_corpus <- Corpus(VectorSource(train_data_df$Text))

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, content_transformer(tolower))

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, removePunctuation)

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, removeWords, stopwords("english"))

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, stripWhitespace)

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, stemDocument)

# create document-term matrix and convert to data frame

train_dtm <- DocumentTermMatrix(train_corpus)

train_dtm <- removeSparseTerms(train_dtm, 0.995)

train_dtm_df <- data.frame(as.matrix(train_dtm))

colnames(train_dtm_df) <- make.names(colnames(train_dtm_df)) That’s it. We can proceed to explain how we intersect this set of terms, given by the column names of the train_dtm_df, with its analogous coming from the new input data uploaded by the user. Once we do that we can train our classifier.

Model selection

Our model selection process is basically the intersection of terms we previously explained. As we said, the idea is to end up with a model in which every input variable (i.e. term) appears in the text that we want to classify.

All the code here will be included in the build_model function within the file server.R.

So as we did with the training data, we start by creating a corpus, using the same set of transformations. Then we convert it to a document-term matrix and then to a data frame that we can use to intersect with the training one.

# Create new data corpus

new_corpus <- Corpus(VectorSource(new_data_df$Text))

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, content_transformer(tolower))

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, removePunctuation)

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, removeWords, stopwords("english"))

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, stripWhitespace)

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, stemDocument)

# create document-term matrix

new_dtm <- DocumentTermMatrix(new_corpus)

new_dtm <- removeSparseTerms(new_dtm, sparsity)

new_dtm_df <- as.data.frame(as.matrix(new_dtm))

colnames(new_dtm_df) <- make.names(colnames(new_dtm_df))Then we do the intersection as follows.

# intersect corpora

common_names = intersect(colnames(train_dtm_df),colnames(new_dtm_df))

new_dtm_df <- subset(new_dtm_df, select=names(new_dtm_df) %in% common_names)

# prepare the training data

model_train_data_df <- cbind(

train_data_df,

subset(train_dtm_df, select=names(train_dtm_df) %in% common_names)

)

# Get rid of the original text that we don't use for training the model

model_train_data_df$Text <- NULL Now we can train our random forest classifier. Of course we train just using the training data. The input data was used just to select terms, never to train the model! Obviously we don’t have labels in the new incoming data, so it doesn’t even make sense to think about it.

model <- randomForest(Sentiment~.,data=model_train_data_df, ntree=50)But why to use a random forest instead of our old linear classifier? Well, the linear classifier was good for interpretation, but now we want a better accuracy. A random forest trains multiple trees for each decision variable, making this method more accurate and less prone to overfitting.

So that is basically everything regarding machine learning in our web application. The next section will deal with how we organise this into our Shiny application.

A Shiny web application

Our Shiny web application is composed of two files. One defined the user interface, and is called ui.R by convention (i.e. the Shiny framework expects that). The other one defines how the server deals with the user interface and executes any required R code. This file is called server.R.

There is an alternative deployment where we have a single app.R file including both parts, but we think the two-file approach promotes better software design practices.

User Interface

Our User Interface will contain four different areas:

- A very simple title area, that will show our application title.

- A control panel area, located at the left hand side of the page central area. There is where the user will indicate what needs to be done and how.

- A result overview area, to the righ of the control panel. There the user will get a global impresion of the sentiment classification results, in the form of a distribution chart.

- A result detail area, at the bottom of the page. There the user will see the classification probabilities for each paragraph in the input text, as a table.

All that is defined by the ui.R file as follows.

library(shiny)

shinyUI(fluidPage(

# Application title

headerPanel("Text Sentiment Analyser"),

sidebarLayout(

# the control panel

sidebarPanel(

fileInput('file1', 'Choose text File',

accept=c('text/tsv',

'text/tab-separated-values,text/plain',

'.tsv')),

tags$hr(),

sliderInput("threshold",

"Positive sentiment threshold",

min = .1,

max = .99,

value = .5),

tags$hr(),

sliderInput("sparsity",

"Max. term sparsity",

min = .1,

max = .99,

value = .95)

),

# Show a plot of the generated distribution

mainPanel(

plotOutput('distribution')

)

),

tags$hr(),

fluidRow(

# the results detail panel

column(12,

tableOutput('contents')

)

)

))As you can see there is a hierarchy of elements. The main one shinyUI includes the main page layout (i.e. fuildPage). Inside that we have defined four different panels:

- The

headerPanelcontaining the title. - The central area with a

sidebarLayoutthat contains two panels. These are: - The

sidebarPanelwith all the controls including afileInputelement for the user to upload input data, and twosliderInputones to fine tune the classification process. The first argument to these alements is always an ID, that every input/output UI item needs to declare. We will use these IDs later on on the server side. The additional arguments are the different configuration values that each element needs. - The

mainPanelthat renders the distribution chart using aplotOutput. - The detail panel, defined as a

columnwithin afluidRow. This elmement just displays tabular data using atableOutputelement.

For a detailed description of layouts and user interface elements, together with its parameters, we refer the reader to the Shiny reference documentation page.

Server part

The server.R file is in charge of dealing with the user interactions and trigger any required computation. It is mainly defined by a shinyServer call as follows.

shinyServer(function(input, output) {

output$contents <- renderTable({

results()

})

output$distribution <- renderPlot({

if (is.null(results()))

return(NULL)

d <- density(

as.numeric(results()$Prob > input$threshold)

)

plot(

d,

xlim = c(0, 1),

main=paste0("Sentiment Distribution (Prob > ", input$threshold, ")")

)

polygon(d, col="lightgrey", border="lightgrey")

abline(v = input$threshold, col = "blue")

})

results <- reactive({

inFile <- input$file1

if (is.null(inFile))

return(NULL)

# load input data

new_data_df <- read.csv(

inFile$datapath,

sep='\t',

header=FALSE,

quote = "",

stringsAsFactor=F,

col.names=c("Text")

)

model_and_data <- build_model(new_data_df, input$sparsity)

pred <- predict(model_and_data[[1]], newdata=model_and_data[[2]], type="prob")

new_data_df$Prob <- pred[,2]

new_data_df

})

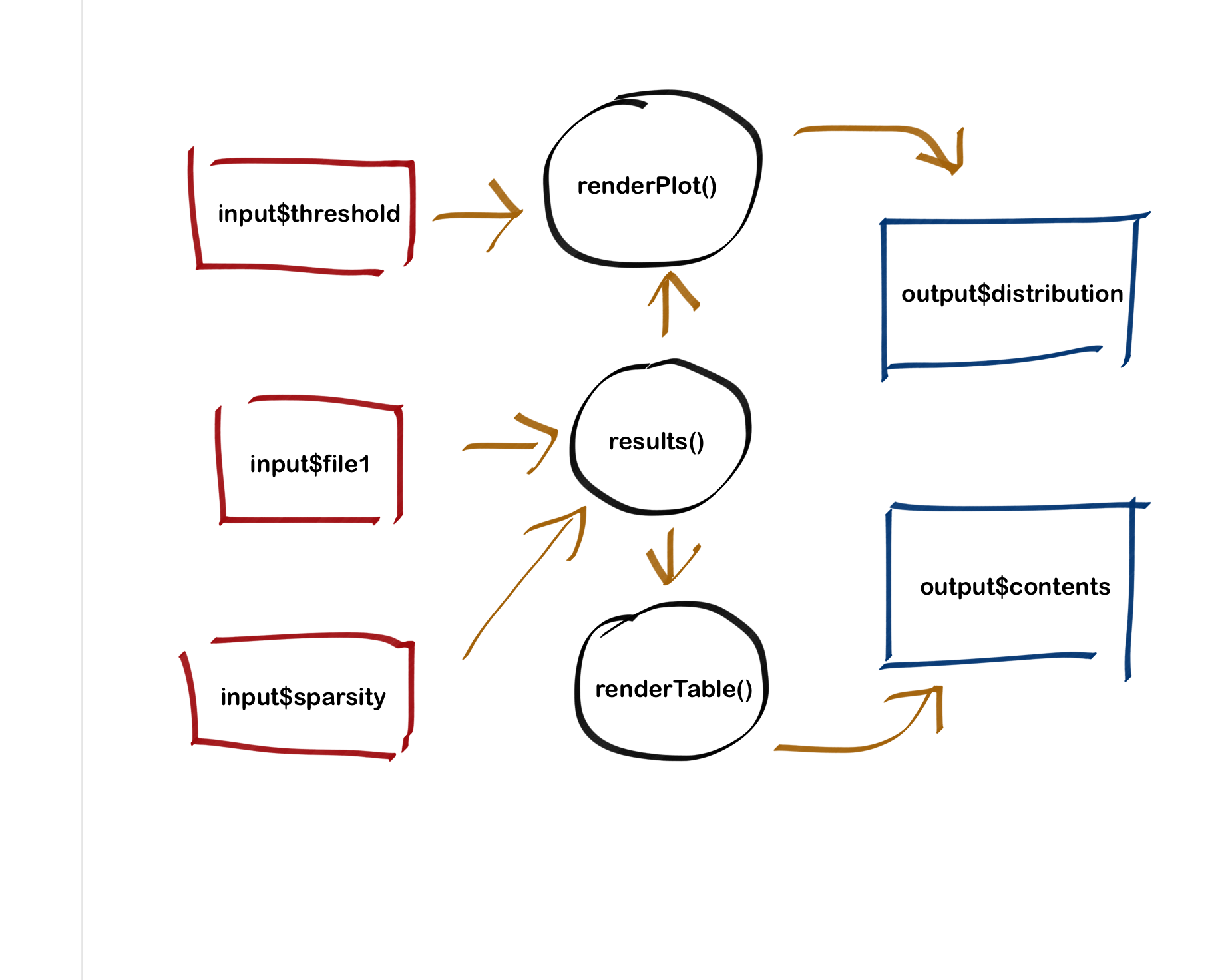

})Don’t panic (yet). We are going to explain this code fragment right now. The call to shinyServer is made by the Shiny application engine when the web page is loaded. It’s passed two variables, input and output. They contain the input and output elements we have declared in the ui.R file and can be accessed as an R labeled list using the $ sign and the ID we defined when declarin the element in ui.R. For example, input$sparsity makes reference to sliderInput("sparsity"... and so on.

So what is inside this shinyServer call? Basically we have made three assignments using the <- operator. The first two are asignments to output elements contents and distribution. They use the corresponding renderTable and renderPlot functions to show tabular and chart data within the elements declared in ui.R. These render functions are what in Shiny are called reactive code. They are executed every time there is a value change for an input element used within that reactive code.

For example, the renderPlot function that is assigned to output$distribution is re-executed every time there is a change in the input$threshold value (i.e. when the user moves the slider).

But we can also declare our own reactive code fragments, and this is what we do in the third assignment when declaring results <- reactive({...}). We are just indicating that we want to re-assign the returning value of the code within the curly brackets to results every time there is a change in any of the inputs (e.g. input$sparsity) used within that code.

And that reactivity is propagated to every fragment that makes a call to `results(). For example, the assignment

output$contents <- renderTable({

results()

})Will be done every time the assignment to results is done, and the table will be re-populated with new results. The same with the plot since there is a call to results() within renderPlot(). In that sense, a change in the value of result will be treated as a change in the input$threshold value. The plot will be rendered again.

But let’s pay a bit more attention to the results assignment, since there is where our model training and prediction happens. Let’s present the code here once more.

results <- reactive({

inFile <- input$file1

if (is.null(inFile))

return(NULL)

# load input data

new_data_df <- read.csv(

inFile$datapath,

sep='\t',

header=FALSE,

quote = "",

stringsAsFactor=F,

col.names=c("Text")

)

model_and_data <- build_model(new_data_df, input$sparsity)

pred <- predict(

model_and_data[[1]],

newdata=model_and_data[[2]],

type="prob")

new_data_df$Prob <- pred[,2]

new_data_df

})So this code will be executed every time there is a change in any of the two input elements used:

input$file1: that is, when a new file is selected.input$sparsity: when the user will change the sparsity slider (that is used to create the corpus as we learnt in the sentiment classification tutorial).

The code itself does three things:

- Loads the input file into a data frame.

- Calls to

build_modelto get a trained model and training data. - Make predictions that are returned as a data frame and therefore assigned to

results.

A change in any of the two listed input elements will trigger the execution of this code and the result will be assigned to results. Any other reactive code (e.g. renderPlot) listening for results() will detect a change in the value and execute iiself if needed.

The code within build_model was explained in the previous section. That leaves the complete server.R file as follows.

library(shiny)

library(tm)

library(SnowballC)

library(randomForest)

options(mc.cores=1)

build_model <- function(new_data_df, sparsity) {

# Create new data corpus

new_corpus <- Corpus(VectorSource(new_data_df$Text))

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, content_transformer(tolower))

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, removePunctuation)

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, removeWords, stopwords("english"))

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, stripWhitespace)

new_corpus <- tm_map(new_corpus, stemDocument)

# create document-term matrix

new_dtm <- DocumentTermMatrix(new_corpus)

new_dtm <- removeSparseTerms(new_dtm, sparsity)

new_dtm_df <- as.data.frame(as.matrix(new_dtm))

colnames(new_dtm_df) <- make.names(colnames(new_dtm_df))

# intersect corpora and prepare final training data

common_names <- intersect(colnames(train_dtm_df),colnames(new_dtm_df))

new_dtm_df <- subset(new_dtm_df, select=names(new_dtm_df) %in% common_names)

model_train_data_df <- cbind(train_data_df, subset(train_dtm_df, select=names(train_dtm_df) %in% common_names))

model_train_data_df$Text <- NULL

# train classifier

model <- randomForest(Sentiment~.,data=model_train_data_df, ntree=50)

# return value as a list

list(model, new_dtm_df)

}

shinyServer(function(input, output) {

output$contents <- renderTable({

results()

})

output$distribution <- renderPlot({

if (is.null(results()))

return(NULL)

d <- density(

as.numeric(results()$Prob > input$threshold)

)

plot(

d,

xlim = c(0, 1),

main=paste0("Sentiment Distribution (Prob > ", input$threshold, ")")

)

polygon(d, col="lightgrey", border="lightgrey")

abline(v = input$threshold, col = "blue")

})

results <- reactive({

inFile <- input$file1

if (is.null(inFile))

return(NULL)

# load input data

new_data_df <- read.csv(

inFile$datapath,

sep='\t',

header=FALSE,

quote = "",

stringsAsFactor=F,

col.names=c("Text")

)

model_and_data <- build_model(new_data_df, input$sparsity)

pred <- predict(model_and_data[[1]], newdata=model_and_data[[2]], type="prob")

new_data_df$Prob <- pred[,2]

# return data frame

new_data_df

})

})

# This is the init code, that will be run when the web app loads

# Load train and test data

train_data_df <- read.csv(

file = 'train_data.tsv',

sep='\t',

quote = "",

header=FALSE,

stringsAsFactor=F,

col.names=c("Sentiment", "Text")

)

train_data_df$Sentiment <- as.factor(train_data_df$Sentiment)

# Create training corpus for later re-use

train_corpus <- Corpus(VectorSource(train_data_df$Text))

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, content_transformer(tolower))

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, removePunctuation)

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, removeWords, stopwords("english"))

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, stripWhitespace)

train_corpus <- tm_map(train_corpus, stemDocument)

# create document-term matrix

train_dtm <- DocumentTermMatrix(train_corpus)

train_dtm <- removeSparseTerms(train_dtm, 0.995)

train_dtm_df <- data.frame(as.matrix(train_dtm))

colnames(train_dtm_df) <- make.names(colnames(train_dtm_df))How to run it

Both, ui.R and server.R code can be found in this repo. The other file you need is the training data, that can be downloaded from the repo app folder. These three files need to be placed in the same folder (e.g. sentimentclassifier).

In order to use the web app you just created you can do two things. You can run it locally using RStudio or you can share it at Shinyapps.io with all of us (with your own modifications, this is ours). This last option can be performed also from RStudio. The IDE (if you use a recent enough version) will detect that you are building a Shiny app when the files ui.R and server.R are present, and will show buttons to run and deploy your app. In order to deploy to Shinyapps.io you need to sign up there first. There is a free account that works perfectly for our purposes.

The input files for our app need to be text files with one or more paragraphs. The file must not contain tabulators, and some other characters might also cause problems (although so far we didn’t experience any).

Take it easy when starting the app. The init code might take up to a few minutes to execute, depending on your machine (less than a minute if running in Shinyapps.io). Moreover, when loading a file there is also a model training process that will take more or less time, depending on the size of the file you are trying to analyse.

Conclusions

We have just show how to create a web app from a machine learning model using R. We made use of some of the techniques we used to build a sentiment classifier in a previous notebook. The web development process should take one or two days, and this is very convenient. True is that Shiny is not the definitive framework for complex web applications, but it is perfect for rapid delivery of data products where the UI is relatively straightforward and the power is in a R model. Personally I see a lot of possibilities for freelancing in it, and also to share results within a company!

So if you have followed our tutorial, now is time to fork the repo and make it yours!